NSF Awards: 1621344

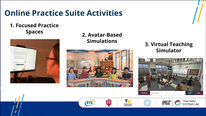

The Common Core State Standards and Next Generation Science Standards advocate for the importance of engaging students in argumentation during mathematics and science instruction to support their learning. However, facilitating discussions that engage students in argumentation is difficult to learn how to do well and a teaching practice that novices rarely have opportunities to observe or practice. This video will share results from a four-year NSF-funded study examining how simulated classroom environments can be used as practice-based spaces to support preservice elementary teachers in learning how to facilitate argumentation-focused discussions in mathematics and science. Presenters will describe how a group of elementary mathematics and science teacher educators integrated a set of newly developed performance tasks into their elementary method courses to support teacher learning. They will also share results from examining preservice teachers’ scores on two summative performance tasks administered pre- and post-intervention and discuss the key factors that supported these preservice teachers’ learning. The video from this final year of the project will highlight the project’s main research findings and discuss what researchers learned about how simulated teaching experiences can be used most productively to support teacher learning.

Heather Howell

Research Scientist

Welcome to our video! We are now in our final year of this project and are thrilled to have results to share.

Speaking of sharing, we recently made all of the tasks and associated support materials we developed on this project publicly available as part of the Qualitative Data Repository, in hopes that this will support teacher educators and other researchers seeking to use math and science teaching simulations in their work. Our file library is extensive and includes everything you would need to enact or adapt these simulated tasks, including training videos, scoring materials, and of course the performance tasks themselves. (The links and instructions can be found at the end of our recent blog posting, or create a free account at QDR then search "Go Discuss".)

We would love to hear from you here in the discussion with:

Looking forward to the conversation!

Remy Dou

Adem Ekmekci

Hello Heather and Jamie, thanks for sharing your study and it's preliminary findings. I think using digitally simulated classrooms is a great idea. I have few questions related to your study.

What software or platform do use for that? Is there a sample video clip of a simulated classroom that also shows how PSTs use it?

The improvement from pre to post is magnificent. In addition, the difference in growth between baseline and formative semesters is also great. It's the same group of PST in the baseline and formative semesters, correct? I was almost sure that they are the same group but the number of PST is different, so, I am not sure. If it's the same group, would it be more informative if exact participants are included in the comparison only?

Sabrina De Los Santos

Remy Dou

Heather Howell

Research Scientist

Hi Adem!

Such great questions. I will try to hit all of them.

For this project, we work within the Mursion platform. We have related work also featured in the showcase that includes a brief clip of one of our researchers enacting a simulation, so feel free to check that one out, but basically the PSTs log into an interface on their own computer and see the 'students' on the screen.

We were thrilled to see strong evidence of learning, although the baseline/formative relationship is a bit more complicated. PSTs don't generally take the same course twice (and if different courses the learning might be more properly attributed to progress in the program than our intervention) so what we kept fixed across the semesters was the course and teacher educator. So, for example, for our first site, the teacher educator taught a baseline section of the methods course in the spring semester with one group of PSTs and then the following spring taught a formative section of the methods course in the spring semester with a different group of PSTs. Our reasoning was that most groups of students are similar in characteristics if its the same teacher, same class, different year, and that collecting baseline data first minimized the teacher educator unintentionally introducing changes to instruction. You can see in the graph that the pre scores aren't exactly identical for the baseline and formative groups, there is some natural variation, but the pre/post improvement held even when we controlled for that difference.

Remy Dou

Dionne Champion

Research Assistant Professor

Thanks for sharing your work! It is very exciting to see such positive results, and I appreciate your ability to reflect on the big takeaways, like teacher educator growth from formative assessment, that you did not necessarily anticipate going into the project. Were there any unanticipated challenges that helped to shape your findings and your perspective on this work?

Sabrina De Los Santos

Remy Dou

Jamie Mikeska

Senior Research Scientist

Thanks for your question Dionne. One of the unanticipated challenges on this project was the extent of training and human resources needed to generate specific and targeted formative feedback to share with each preservice teacher (based on his or her video recorded discussion performance). Building on the current research and literature, we developed a scoring rubric and rater training materials focused on five dimensions of high-quality argumentation-focused discussions (e.g., eliciting student ideas; promoting peer interactions; etc.). Raters not only scored each video based on these five dimensions, but also wrote formative feedback linked to each dimension for each video to identify strengths and areas of growth for each preservice teacher. These formative feedback reports were used by both the preservice teachers and their teacher educators during the formative semester, and they are one of the reasons we hypothesize we saw the growth that we did in the formative semester. The formative feedback is also something that we think is important as part of a larger cycle of enactment to support teacher learning and are interested in examining how the nature and type of the formative feedback, including self-reflection, influences teacher learning from the simulated teaching experiences.

Remy Dou

Sabrina De Los Santos

Research and Development Associate

Thank you for sharing this important work. I love the idea of simulated teaching. Did teachers influence the content of the simulated teaching experiences? Now that you are in the final year of the project, do you have plans to continue this work and engage other teachers?

Remy Dou

Jamie Mikeska

Senior Research Scientist

Hi Sabrina -- Thanks for taking a look and for the questions. Teachers definitely influence the content of the simulated teaching experiences in a few ways. First, we had teachers (both current and retired) who were a part of our mathematics and science task development teams from the very start of this project. As part of the task development teams, they helped to decide the content focus of each of the eight performance tasks, including the student learning goals for each discussion and the student work that we embedded in each task. Second, when the preservice elementary teachers engage in the discussions in the simulated classroom, they influence the direction of the discussion in the simulated classroom and the content that is (or is not) addressed throughout the 20 minute discussion. The interactor (that is the human-in-the-loop who is trained to act and respond as the five student avatars during the discussion) is trained to follow each teacher's lead during the discussion and to engage with the content, as prompted by the teacher during the simulated teaching experience. As for next steps, we are hoping to build out a similar set of performance tasks at the lower elementary level (K-2) and study the use of those tasks within educator preparation programs. We are particularly interested in examining under what conditions and for what purposes (e.g., use of different simulation use models and/or types of feedback) using these types of experiences supports teacher learning. We are also interested in expanding into the in-service teacher space to see how such experiences could be embedded into professional development and teacher communities of practice.

Sabrina De Los Santos

Remy Dou

Libby Gerard

What a great video, thank you for sharing your work! I would love to learn more about how the simulations worked particularly how you pre-authored student responses. I also teach pre-service teachers and would love to build on your work. Could you share an example of one of the simulated tasks?

Remy Dou

Heather Howell

Research Scientist

Thank you:) The pre-authoring was a mix of processes. In most cases we drew on the literature around common student approaches, although in some cases what we wanted to represent was unconventional student approaches (to simulate the common teacher challenge of responding to the unexpected) which gave us less to draw on. We elicited feedback from content experts at various points along the way with one question always being about the authenticity of the student responses and approaches, and in the early days we 'tried out' a couple of the tasks - not the teacher tasks but the embedded student challenges - with children to get a sense of whether our language and wording on the topics was in line with how kids actually talked about the work.

As far as examples, you can see all the examples, they are posted online in the qualitative data repository (instructions to get access are in my first post at the top) but if you try and run into any difficulties drop me an email and I'll help. hhowell@ets.org.

Remy Dou

Libby Gerard

Thank you for sharing. I am now exploring the data in the repository. This is a fantastic resource. I will look into adding some of our data here as well.

One more question - are the interactions using a machine learning approach to determine the responses of the avatars (based on the PST remarks), or is a human playing the part of each of the student avatars in real time? If it is the latter, what do you find are the advantages of simulating the interactions in the computer, versus doing it "live" in the classroom?

Heather Howell

Research Scientist

I'm so glad you were able to get to the data. This is our first time using the resource, and its such a fantastic tool for getting the work out there into the world.

In this work, a human is playing the part of the student avatars - in fact one human is playing all five avatars. Although its computer aided in the sense that there are some automated movement sequences to manage things like the whole group raising their hands, voice modulation to make sure they all sound different from one another and consistent across various actors, etc. Remy commented about this as well and I'll talk a bit more about machine learning in that response.

Carrie Straub, our co-pi at Mursion, wrote a nice white paper that outlines the pros of working with simulated students in general as an approach.

From my point of view, probably the most important advantage is simply your control, pedagogically, over what the teacher in the simulator is faced with or asked to do. There are a number of scholars who work on what I would describe as rigorous rehearsals, in which significant time goes into helping preservice teachers act as children would for the benefit of their peers who practice teaching them, but I'd say that is not the norm - in most cases the teachers do their best but, given that they are not trained actors and are just starting to learn how children think, representing children authentically is quite difficult, as is not giving into the inevitable urge to help your peer by learning. Because the actor on the back end is trained extensively they respond much more authentically to how children might, and more consistently, meaning that whatever dilemma of practice I've decided as a teacher educator that I want my preservice teachers to face, I can feel sure that each and every one of them will encounter that dilemma.That has mattered immensely in our work, because preservice teachers opportunity to even observe argumentation-focused discussions, much less really dig into leading them, is so limited in field placements that you could wait a whole semester hoping it would happen once for each of your preservice teachers and find that it didn't for most of them. The simulator means you can guarantee it happened for every single one of them the same week, at the moment that makes sense within your course planning. I would also argue (but just my opinion) that given the cost of the technology this is why it makes sense to use it to simulate the types of ambitious instruction that we want to see more of but don't yet, making it hard to provide preservice teachers the type of support they need to enact it. Thats probably where the payoff is highest.

In terms of authenticity, the students definitely look animated - no one would mistake them for real people - but in truth its not more of a stretch to imagine them as real than it is one to imagine your classmates as children.

Remy Dou

Assistant Professor

Comments: In my own teaching practices I often find myself limited in my ability to situate pre-service teachers within authentic contexts that support their ability to apply the skills they're learning to the "real-world". I'm encouraged by the development of technologies like this one that facilitate authenticity and the positive findings associated with its use.

Questions: I'm curious about the extent to which the technology presented here (or similar technology) incorporates or can incorporate artificial intelligence in their algorithms. In what ways and to what extent has this been considered? Could AI support more authentic interactions with the technology? What challenges exist in developing AI for technologies like this one?

Sabrina De Los Santos

Heather Howell

Research Scientist

The AI question is such a timely one. The technology we work with (Mursion) is what I describe as non-artificial intelligence, as in, human beings driving the simulation behind the scenes. A bunch of folks are working toward AI interactions in this space, and it seems like the natural next step but it also doesn't seem like we are quite there yet. AI does pretty well on interactions that are tightly scripted but a dialogue between 6 players, even if five of them are artificial, and even constrained to one scenario, can play out really differently across a 20 minute time span. We've been exploring what it would take to produce automated feedback, building on the work we did in this project to score and provide feedback to the pre-service teachers based on their video-recorded teaching sessions. Even that is complicated, and it doesn't have to happen in the moment with instant speech recognition the way it would need to to drive the conversation itself. My hunch, although I could be wrong, is that what will happen first is that AI will make progress in analyzing common patterns of recognition in fits and starts, unevenly, with more success in recognizing some patterns than others, but that this might provide really useful feedback loops to the interactors (the actors who control the avatars) by prompting them with various responses to consider based on what the teacher has just said, still allowing them to make final judgments about what makes sense in the moment but providing a support to mitigate some of the cognitive load this work places on them.

In terms of challenges, I don't have a background in machine learning, but having had a lot of conversations I'd say almost certainly one answer is that we can train machines to do a lot of things, possibly anything, if we work at it and have enough data, but that is a significant challenge when your data point is a 20 minute long video that is fairly expensive to come by. Over the five years of this project and a couple of related ones, we have in hand a couple hundred videos that are usable for this type of analysis, which is a huge data set from the standpoint of educational research and small potatoes in the machine learning world.

Sabrina De Los Santos